Not a very long long time ago, the realm of education was consumed by a persistent concern over what it didn’t know. The yearning for a complete picture, a comprehensive understanding of students and their progress, drove the relentless pursuit of data. However, in this age of information abundance, a new challenge has emerged. Education now finds itself facing a different dilemma—not a scarcity of data, but an overwhelming surplus. More data, more systems, more analysis have flooded the educational landscape, promising insights and answers. Yet, amidst this sea of information, clarity and thoughtful interpretation can often become elusive. The allure of ‘safety in numbers’ beckons, but we must tread carefully, lest we become entangled in the web of data overload, losing sight of the true purpose: using data effectively to drive meaningful change. As we navigate this landscape, the concept of ‘safety in numbers’ takes on a different meaning—one that calls for discernment and focus rather than being carried away by the sheer volume of information.

Collecting data has become second nature from assessments to behaviour, the systems for data collection have grown exponentially. The prevailing belief is that more data leads to greater understanding and better decision-making. However, amidst this relentless pursuit of data, one critical aspect often gets neglected—the need for meaningful reflection and analysis. It’s not just about collecting data once and using it many times; it’s about collecting data once, thinking about it properly at least once, and using it to help inform discussion in a meaningful way.

Teachers, at the heart of the classroom, possess a wealth of knowledge and experience that cannot be replaced by any data collection system. They understand their students in ways no data point can capture. Sometimes danger lies in relying solely on data to shape our perceptions and decisions. Data should serve as a tool to enhance our understanding, complementing the insights gained through personal connections with students. It should not overshadow the importance of human judgment, intuition, and empathy that teachers bring to their classrooms.

Amidst the abundance of data and the myriad of systems designed to display it in a thousand different ways, the risk of losing focus and direction is real. Schools may find themselves drowning in an ocean of numbers, struggling to discern the signal from the noise. While data can highlight trends and patterns, it is the actions we take that truly make a difference. Merely being surrounded by data does not equate to using it effectively.

As schools continue to navigate the complexities of data usage, it is paramount to strike a balance between quantity and quality, between being overwhelmed by data overload and using data purposefully. The allure of “safety in numbers” can lead us astray if we fail to focus on actions rather than distractions. By collecting data once, thinking about it properly, and valuing the unparalleled knowledge of teachers, schools can transform the overwhelming array of data into a catalyst for positive change. Let us embrace the power of data without succumbing to its overwhelming presence, using it as a compass to navigate the path towards improved student outcomes. By keeping our focus on what truly matters—the growth and success of students—we can harness the potential of data and wield it as a force for meaningful transformation in education.

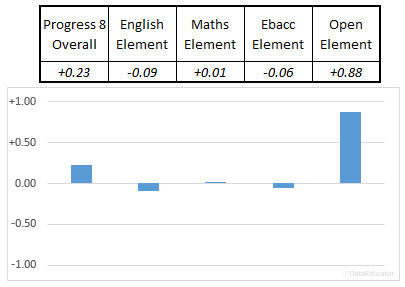

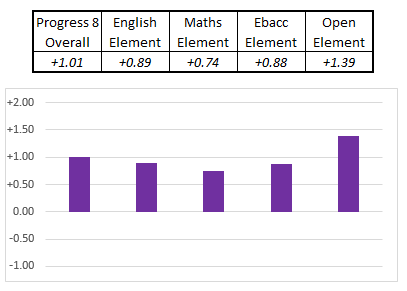

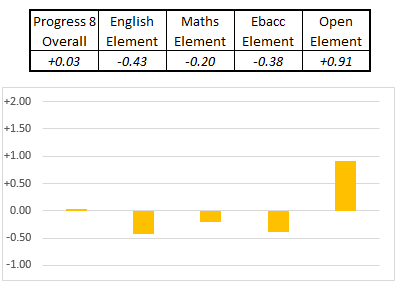

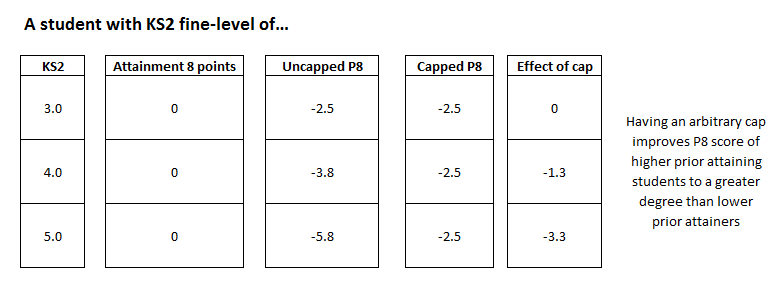

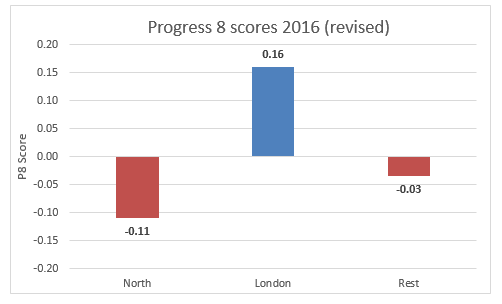

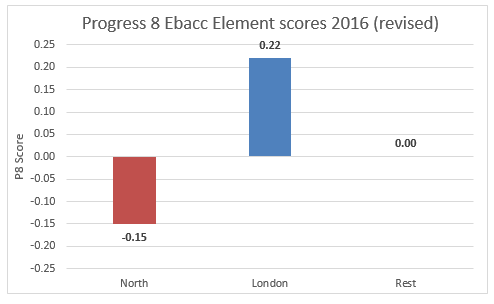

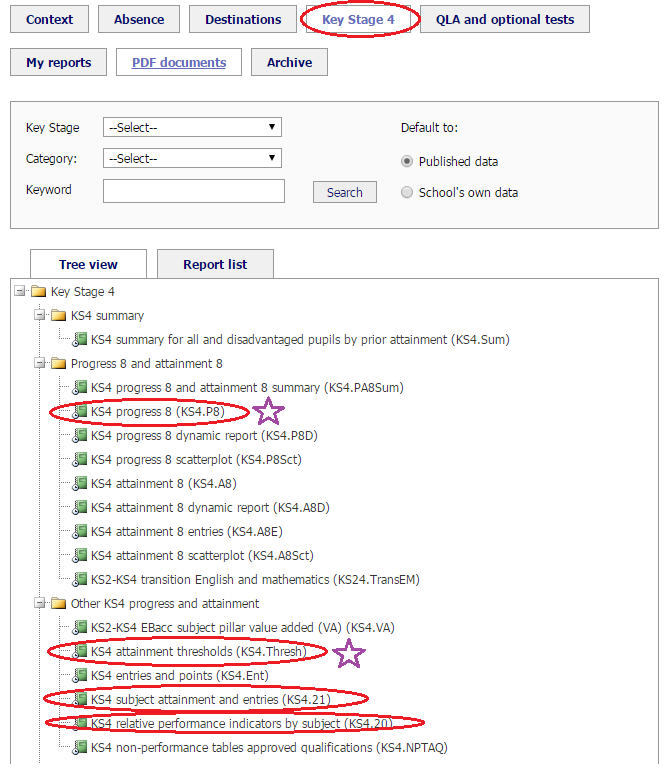

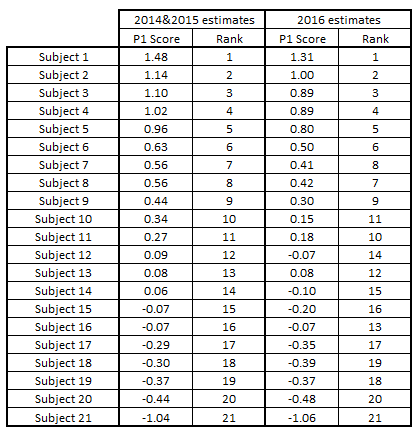

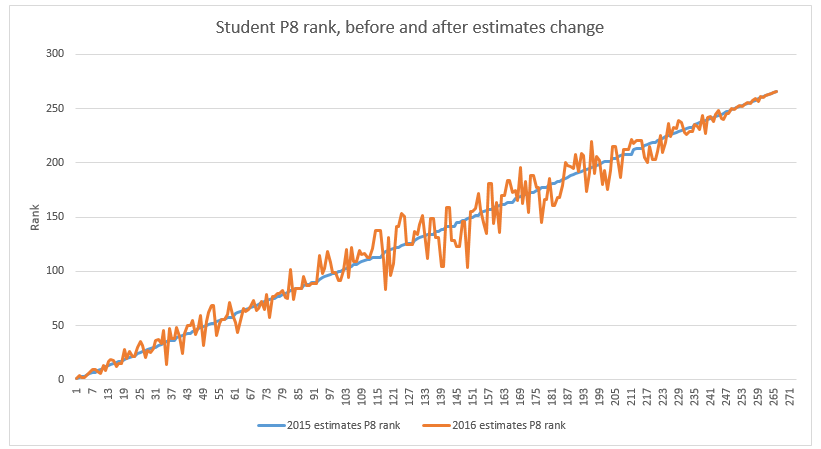

I believe that this framing of data is vital as we head towards yet another period of turbulence in secondary data, as we will shortly no longer have progress 8 (due to lack of starting points) and obviously therefore KS2 outcomes as a crutch on which to lean and to use as the basis of discussion. One option would be to try and replace that information with something similar from another source, and many schools will attempt just that, however energy could be better served by not investing in more made-up information and instead focusing more on what differences can be made to tangibly help students in the here and now. In short, revisit your mindset and not your dataset.

And perhaps… in my version of this fairy tale – we’ll all live happily ever after.